The Latest in LAM Science: Q & A with Kathryn Wikenheiser-Brokamp, PhD

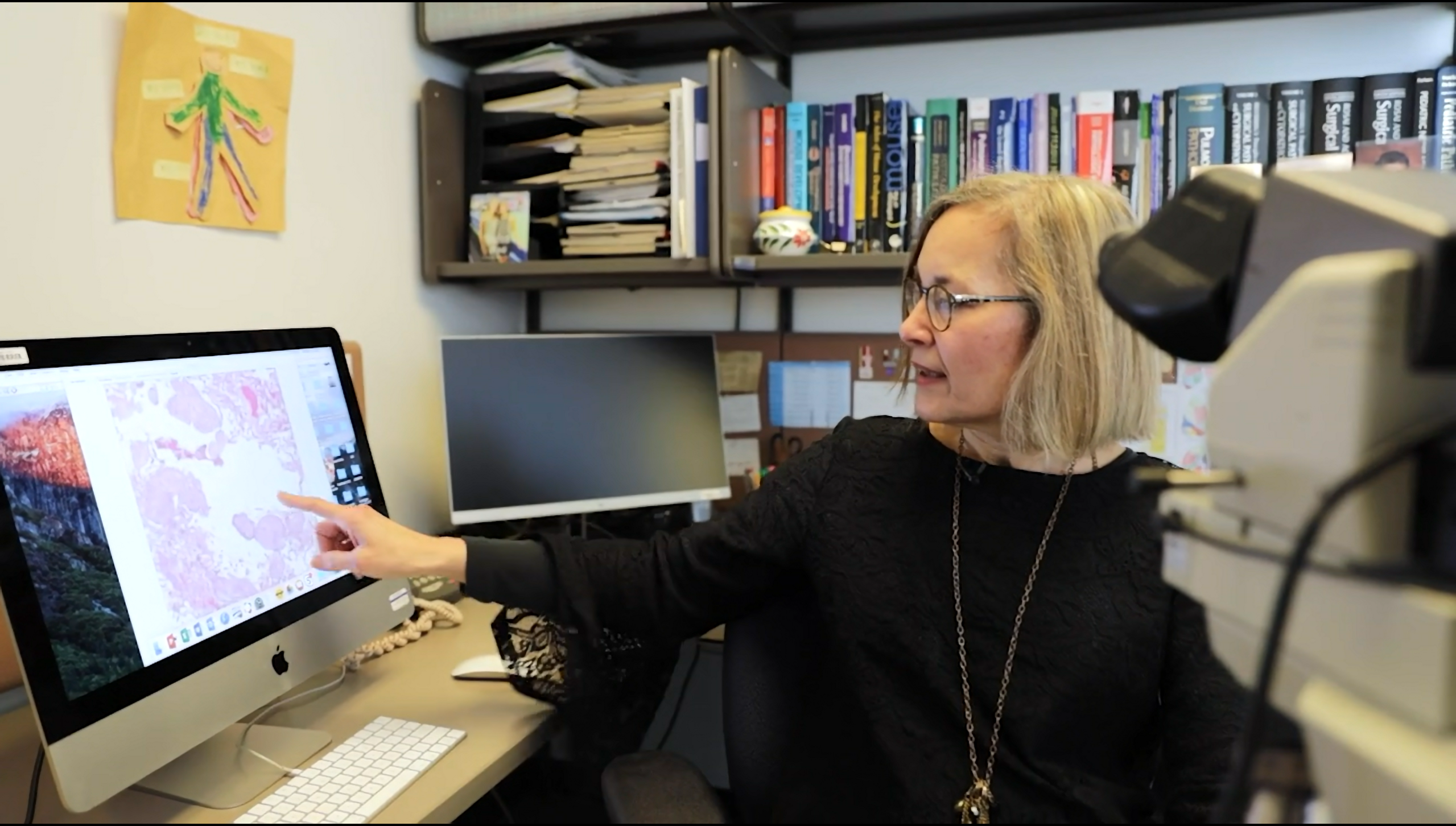

Dr. Wikenheiser-Brokamp of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center was awarded an Established Investigator Award in 2022 for her project titled: Identifying Cell-Cell Signaling Driving Pulmonary LAM Pathogenesis Using Spatial Omics Strategies

The below interview is edited for length and clarity.

TLF: How did you start studying LAM and connect with The LAM Foundation?

KWB: I’m trained in both research and in medicine as a physician-scientist pathologist, so I diagnose disease by reviewing tissues. My background is in researching lung development and lung disease. When I came to Cincinnati for my first faculty position, I had the unique opportunity to review and diagnose LAM lungs from patients referred to me by Frank McCormack and Nishant Gupta. From a scientific point of view, reviewing tissues raises a lot of questions that are very interesting to explore. Ultimately, however, I got “trapped” into studying LAM when I went to a couple of meetings and met the patients with LAM and their families. They motivate me and give my work purpose. I find enjoyment in working with patients and their loved ones and thoroughly believe that advancement is optimally accelerated when clinicians, scientists, and patients work together.

TLF: Can you please explain the title of your project?

KWB: The easiest way to think about it is that the LAM lung is comprised of many different components that are called cells. Think about it as a fruit salad. Each piece of fruit in the salad is a different cell that are all mixed together. But then if you take the salad and you make a fruit tart, you arrange the fruits in a specific pattern that gives you a whole different picture, the tissue. What I and my collaborators Yan Xu, Jane Yu, and Frank McCormack did in the past was take the lung with all those different cell types that are interacting with one another and dissociated them creating a fruit salad. We found out that every single piece of fruit or cell had a specific gene expression pattern by single-cell RNA sequencing. Now we know the identity of all the cell types in the LAM lung and what they could be saying to each other, but we don’t know how the cells are interacting with one another since we don’t know which cells are neighbors. We’re now examining the LAM lung tissues with their neighborhoods intact so that we can not only determine what each cell is saying but also who is near them to listen to the message. We are examining the LAM tissue spatially to determine what every cell is saying and where they’re located, so that we know which cells are talking to each other.

TLF: Are you speaking about general lung tissue or only LAM tissue?

KWB: We are focusing on examining LAM tissue and then comparing what we find in LAM lungs to what is happening in healthy lung tissue. I’m selecting LAM tissues that have cysts, diagnostic LAM cells, and lymphatic vessels that help the LAM cells travel to other locations. We believe that if we understand how the cells making up these characteristic alterations in the LAM lung are talking to each other, we’ll understand why the lung in LAM patients is destroyed to form cysts and how the LAM cells get into the bloodstream to move to other locations.

TLF: Would you say the logical next step is to figure out how to interrupt that conversation?

KWB: Yes. That’s the whole goal. If we can understand how the cells communicate with each other and what signals they’re using to cause lung destruction, we can devise new ways to interrupt that signal with targeted drugs or possibly other types of treatment. By understanding the cells better, we can also devise strategies to better diagnose patients and monitor how they respond to treatment. If some of the signals we find are secreted into the blood or into the airways of the lung within the bronchioalveolar lung fluid, we could use these biomarkers to diagnose patients and determine the extent of lung destruction in individual patients to guide personalized treatment and tell us whether their current treatment is effective.

TLF: The scientific leadership of The LAM Foundation has described your research as cutting-edge. What are your thoughts about that?

KWB: Well, it is utilizing state-of-the-art technology. We can do things that we could never do before. We can look at each cell and determine whether they are expressing over 18,000 different genes. We can do that on a piece of tissue, so we can determine how close the cells are located to one another and how they are giving and receiving information. That’s very powerful technology that has just come out in the last year. Spatial transcriptomics allows us to select a specific piece of tissue, examine it at a microscopic level, and then digest the tissue on the slide and see every gene that every cell is expressing while maintaining its location within the tissue. Thousands of little circles are placed over the tissue, and we can determine what each cell in each little circle is saying and which cells are receiving the messages. We can then construct a picture showing the cells in their tissue environment overlaying all the genes each cell is expressing to talk with the cells around them. You can look at the tissue section and say this cell is expressing these 400 genes and it’s right beside another cell that’s expressing these 600 genes. Yan Xu, who is the Co-Principal Investigator on the TLF grant with me, is bioinformatically analyzing this data. She takes the myriads of data resulting from the spatial transcriptomic analyses and using sophisticated computer algorithms puts all the data together in a format we can interrogate to discover the unique cell-to-cell communications in the LAM lung and how that communication differs from what is occurring in a healthy lung.

TLF: What would you say is the next generation of LAM research?

KWB: Translating the information learned from single-cell technologies into novel diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic strategies for patients. The ability to determine the signaling in each patient’s tissue opens the door for personalized and targeted therapies to enhance treatment effectiveness and minimize harmful side effects. The first step in this new era is making a dictionary of each cell and what each cell is communicating in its distinct environment, which we are doing now. The explosion of new technology in the last few years has opened up opportunities that we have never had before. We are taking our understanding of the LAM lung to the next level by understanding each single cell in the context of its neighbors.

TLF: What would you like to see come from the research that you’re doing today?

KWB: Advanced care for patients with LAM to improve their lives and the lives of their loved ones. We know the TSC mutation is present in only a minority of cells in the LAM lung. This minority of LAM cells however must be talking to a lot of other cells to destroy the lung resulting in lung cysts. It is possible that if we could eliminate these few cells or block the signals they use to alter the function of other cells we could cure LAM or stop disease progression. How do we identify and kill these cells? Do they need something from the other cells to keep them alive? We know that when we treat these cells with sirolimus it stops them from growing, but can we get rid of these cells using a different treatment? By determining how the cells talk to each other, we may also be able to determine why sirolimus is effective in some patients but not in others. We could then use these cell signals that indicate that sirolimus won’t work to determine which patients will respond to this treatment and which patients need different treatment. That will personalize care for patients with LAM and avoid patients from suffering side effects of treatments that aren’t effective for them. Our goal is to identify patients who need treatment, get them on treatments that are effective for them, and devise strategies to monitor treatment effectiveness. It is my hope that our studies will move us in the direction to accomplish these goals.

TLF: There’s one key factor that enables you to do what you do – the availability of LAM tissue from transplant patients.

KWB: You are absolutely correct. None of our work would be possible without the generosity of the patients and their families who donate their tissue for research. I’m really passionate about thoroughly examining LAM tissue because I believe the tissue holds information we need to attain our goal of advancing care for patients with LAM. None of our work is possible without the patients joining us in the research by donating their tissue. Our initial single-cell studies required that we get LAM tissue from the operating room and into our hands in less than 72 hours. The LAM Foundation and the patients made that happen. I don’t think that the patients and their loved ones realize fully how they’re driving this research. It could not be done without them. Thank you to all the patients and their loved ones who make our studies possible.

###